In almost every transformation, you will hear at some point that it is important for the organization to change its culture, values, and/or behaviors. The key to a successful (digital) transformation lies in driving behavioral change among individuals and fostering a willing-to-change environment.

The importance of behavioral change is becoming more prominent in transformations and with its broad scope over the years the list of books, articles, and change models is only growing. Although we are happy with the attention this topic is now receiving, this does come with the risk of misunderstanding one another when it comes to defining what we mean by certain behavior. Behavioral change is a concept (mis)used by many change-driven leaders and one that leaves a lot of room for interpretation. To begin with, it is crucial to cut through the noise of various definitions of “behavior” and find the right one. Many discussions around behavioral change fail to establish a common definition of “behavioral”.

There's a risk of treating behavioral change as an afterthought and already starting with designing a transformation journey. Furthermore, you also need to avoid ordinary behavioral-change pitfalls to become extraordinary change-oriented leaders. Keep scrolling to find out how and let's get started with unraveling the complexity and talking about behavioral change in a practical way!

Your starting point: specifying “behavior”

As leaders, we often use abstract terms such as mindset, culture, behavior, and motivation interchangeably to promote change. However, the effectiveness and the results we try to achieve are not always as we expect. For example, the term ‘effective collaboration’ can have a thousand different interpretations and explanations in terms of behavior depending on who you ask. Therefore, if we genuinely want to change behavior, creating mutual understanding, although challenging, is key to defining a working and lasting change strategy. In that sense, we opt for a single and practical definition based on the extensive wisdom from the field of behavioral science.

The definition we use is based on B.F. Skinner's research: "Behavior is what an organism is doing, or more precisely, what another organism can observe it to be doing". Note the emphasis on OBSERVABILITY —something that can be seen or heard. This definition excludes all internal behaviors and focuses solely on behavior that can be observed by others in the environment.

Focusing on “Observability” facilitates objective communication and helps avoid subjective biases that are inherent in human thinking. As human beings, unfortunately, it’s unavoidable to form subjective and assumption-free interpretations of someone else’s behaviors. This prevents us from truly understanding and explaining behaviors objectively and hinders us when we try to analyze behavior. Skinner’s definition tries to eliminate any interpretations or assumptions. You simply describe what you see or hear.

The second thing worth mentioning about this definition is that behavior is described as an active procedure1. Just sitting, attending, or existing is not considered behavior following this definition and neither is someone not doing something. Instead, the behaviors we observe involve individuals actively doing something—writing, speaking, creating, walking, and so on. This will help us analyze current or future desires and also find out what are our current undesired behaviors

Behavioral science to the rescue!

You may be wondering why we choose these specific definitions of behavior. Well, eventually you want to start with specifying and analyzing behaviors. From a behavioral science perspective, you can only analyze what you can observe. In the end, you’re aiming for a behavioral change which means you need to understand what behaviors are currently present and which are missing to successfully change. This is truly your starting point and the most important part of your change strategy: Specifying the behaviors that are needed for your change! What does it look or sound like? What do people do or what do they need to be doing? How can we promote desired behaviors and demote undesired behaviors? It all starts with Specifying and Analysis!

Behavioral science is to the rescue again!

The field of behavioral science brought us several helpful tools to analyze behavior, based on Skinner’s definition mentioned above. These tools don’t only help us to understand and explain behavior, but also help us to develop strategies aimed at reinforcing desired behaviors and mitigating or eliminating undesirable ones. Plus, this definition enables us to specify the exact behaviors we aim to introduce into the environment, and it helps us to communicate these behavioral expectations without any form of judgment or prejudice. Now that’s a win!

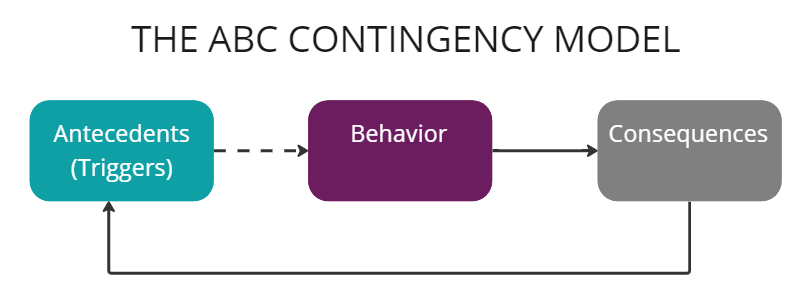

The most influential tool is probably the Antecedents-Behavior-Consequences (ABC) contingency model of Psychologist Dr. Albert Ellis, which provides a simple model that provides many insights. The model explains what precedes behavior but also what consequences follow a behavior. With this knowledge, you as a leader can add or remove both Antecedents (triggers) and Consequences into the environment and start changing behaviors.

Figure 1: The ABC Contingency model

Figure 1: The ABC Contingency model

Figure 1. The ABC model describes what precedes and follows behavior. It is a useful tool to understand and analyze behavior. You can analyze current undesired behavior, current desired behavior, and/or future desired behavior. It helps identify what you can add or remove from the environment to reinforce or stop certain behavior. NOTE, the analysis is always done from the perspective of the performer!

Avoid ordinary pitfalls to become extraordinary change-driven leaders

The bad news is, your starting point - specifying behavior - can be challenging and requires practice!

There are many pitfalls that you want to avoid when you are starting with specifying behavior and we will discuss a few that should be on top of that list. Remember, avoiding these is hard! The key to doing so successfully lies in following the rules:

-

Behavior is ALWAYS about the perspective of the person showing the behavior

First and foremost, it is essential to recognize that the behavior displayed by someone is not about us as observers (behavioral change is not about you!). This means that when analyzing someone's behavior, we must solely consider the perspective of the person showing the behavior and disregard the impact of their behavior on us. You don’t really matter in explaining this behavior. Sorry, not sorry.

The reason we need to detach ourselves from interpreting the behavior of others is that an individual is showing a certain behavior because they are interacting with their environment. As a result of showing this specific behavior, the performer will experience a specific set of positive and/or negative consequences. FOR THEM! The performer will decide if the consequences from the environment are positive or not and whether the behavior is worth repeating again. It doesn’t matter if you think these consequences are positive or negative, it’s about the perspective of the performer! They will decide!

Behaviors are (un)learned through this feedback loop: If a behavior leads to favorable outcomes for the performer, it is likely to be repeated; if it results in unfavorable consequences, it will probably be avoided in the future. So, the primary rule is to always interpret the behaviors and the results of exhibiting these certain behaviors from the performer’s perspective.

02 - Stick to what you can see someone do or hear someone say

As mentioned before, when observing behavior, it's crucial to refrain from making assumptions or linking interpretations to what we observe. Thinking about this scenario - when someone looks at their phone during a meeting, it can be very tempting to interpret that this person is being disengaged or bored, but this is exactly what you should avoid doing! The behavior you’re observing is someone looking at their phone. Period! Nothing more, nothing less. Bear in mind that you should keep your interpretations to yourself. Again, it’s not about you!

By avoiding the interpretation of behavior, you enable the performers to explain and share the actual consequences their behavior holds for them. This provides invaluable insights into what motivates specific behaviors and, furthermore, guides you in reinforcing or discouraging these behaviors through environmental changes.

03 - Can you show me?

When we encounter ‘passiveness’, we often label this as behavior. The problem with this is that passiveness is often an interpretation of the observer, and you don't observe anything! For example, if you feel like people are not participating in a meeting, what active behavior are you then observing? You will find that this becomes tough to describe and even harder to analyze. To get rid of the inactivity we can instead analyze what future behavior we do want to see more of! For instance, you want everyone in the meeting to ask questions. Or do you want everyone in the meeting to take notes? A simple trick you can apply to check whether you have specified active behavior is to ask the question: Can you show me? Or can you act out what you would be doing?

Final disclaimer

One final disclaimer here: you are not a magician! You are not changing people you can only change the environment they are interacting with. So, ‘behavioral change’ here refers to changing the environment in such a way that people are enabled to exhibit desired behaviors.

Ok, now what?

Now, you might be wondering what's next. Behavioral science models can assist you in analyzing, understanding, and changing behaviors. There are various analyses you can conduct to gain insights, but it all begins with observation and specifying. Our advice is to pick one single behavior and engage with the individual(s) involved (Yes, in this case, you can start with yourself!). Explore with the individual(s) what triggers the behavior and what consequences are associated with the behavior. This analysis will enable you to modify the environment to encourage desired behavior while discouraging undesirable ones and create validated strategies to do so.

Curious to see how you can design and strategize for behavioral change? Stay tuned for our next article: Design for Behavioral Change: The Power of Consequences.

Source: Skinner, B. F. (1938). The behavior of organisms: an experimental analysis. New York: Appleton-Century. doi:10.2307/1416495.